- Home

- Sosin, Danielle

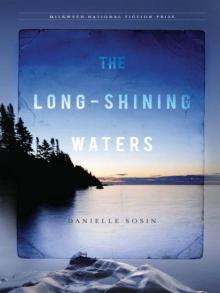

The Long-Shining Waters

The Long-Shining Waters Read online

Table of Contents

Also by Danielle Sosin

Title Page

Dedication

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

1902

2000

1622

1902

2000

1622

1902

2000

1622

2000

1902

2000

1902

1622

1902

2000

1902

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

1902

1622

2000

1902

1622

2000

1902

1622

2000

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

2000

1902

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

2000

1902

2000

1622

1902

2000

1622

2000

1622

2000

1902

2000

1902

2000

2000

2000

Author’s Note

Acknowledgements

More Fiction from Milkweed Editions

Milkweed Editions

Copyright Page

Also by Danielle Sosin

Garden Primitives

For

Lucien Orsoni . . . “for the cry-eye”

and for

My father, Henry Sosin . . . for always

The eagle, the eagle

Patient like him

From the rocks on high

You will perceive a lake . . .

From an Ojibwe hunting song

1622

The cold wind off the lake sets the pines in motion, sets their needled tops drawing circles in the sky. It cuts through boughs and they rise and fall, dropping snow that pits the white surface below. The hardened leaves rattle and sail, and the limbs of the paper birch sway, holding the sky in heavy wedges.

The dark bundle, like the nest of a squirrel. Dark bundle, tiny corpse, lurching with the branches against the sky as the big water, Gichigami, slings against the shore. Spray over icecovered rocks.

In long dark lines, the waves advance, crowding together as they near the shore, mounting and breaking over themselves, leaping at the rocks like wolves. The wind keens, causing branches to knock and deadfall to creak in the frozen forks of trees. The dark bundle rocks on its limb, in the dark sky, above trackless snow.

The waves like wolves leap over each other, toss sea foam from their open mouths. They hit the rocks and fall back again, only to rise howling and leaping, hitting and falling back again, until one after another they paw over the rocks, escape from the churning water, pads icing up in the snow, yellow eyes and patches of grey fur blowing.

Surging, they leap into the woods, dark lips curled over bared white teeth, toward the tree where the bundle churns in the sky. Yellow eyes and blowing grey fur, cracking branches, cold dry wind in their teeth.

Her hand. The woven mat. Night Cloud’s sleeping back. Dreaming. Another dream. Grey Rabbit’s eyes dart like tiny fish as crouched wolves shift shape around her, expanding in edgeless and rolling shadows. The wigwam is full of the heavy sounds of sleep: her two sons, her husband, his mother.

Grey Rabbit blows at the fire, causing the embers to sparkle orange and ash to lift like feathers from the coals. Again, and the new wood crackles into flame. Her family lies undisturbed, their feet pointing toward the warmth. The air is close. Night Cloud’s low snore. All the bodies softly rising and falling as if she were rocking in a sea of breath. Breath and shadow moving the bark walls. The fire whistles, but no one stirs.

Since the first snow of winter she’s seen children in her dreams. In danger and in death they come to her, taking the place of rest and worrying her days. She crouches near her two sleeping boys. Standing Bird looks strong and defiant, the jut of his chin set toward manhood even as his spirit journeys. But Little Cedar, limbs askew beneath the furs, looks vulnerable and warm cheeked. His eyelids flutter and then stop moving. She searches his face for traces of hunger. Again, Night Cloud returned without game.

The corpse, abandoned, sways on a limb. The heavy sky. The sharp-toothed wolves.

She won’t speak of the things she’s shown at night. She won’t tell anyone about the children of her dreams. She smoothes the hair off Little Cedar’s forehead. Her family needs her, especially now, with the food cache dwindling and no fresh meat to replace what they take. She’ll walk steady as the sun for them, even as the specters of winter sweep down.

Quietly, Grey Rabbit feels through her pouch, clasps for a moment the banded red agate that Little Cedar gave her. She draws a heavy fur around her shoulders and ducks out into the darkness.

Bullhead rolls over to see the door flap close, feels the cold air sweeping in. Again, her son’s wife leaves in the night.

Grey Rabbit stands motionless until the fire pit emerges, and then the first ring of pines with their high jagged tops that point like arrows to the sky. Her path cuts through low spruce, then rises along the birch-covered slope that protects their camp from the north’s killing winds. She tries to make her way in silence, to draw no attention in her direction, but her skins swish against the snow as she moves through the vertical weave of white trunks.

The ridge is home to massive old pines. She can feel their reaching boughs above her, feel the thinness of her skin. The grove possesses a frightful strength, yet she has always sensed goodness in its spirit. She rests a moment against the rough trunk of a tree, her heart drumming in her ears, then makes her way to the windswept ledge.

The shore below is ice locked and still, strewn with boulders cleaved from the cliff. The last time she’d come, Gichigami was raging. She’d made her offering despite her fear, there, in the presence of the underwater spirits and the one who churned the waters with his serpentine tail. The waves were smashing against the rocks, wild like hair, swirling white, whipping strands, and the water leapt and pounded, shattering the moon.

Grey Rabbit kneels and digs down through the snow. She places tobacco on the cold rock and a birch-bark dish that holds a small bit of the good berry. She opens herself to Gichi-Manitou, the Great Mystery, as the wind blows cold against her face, and her nose stiffens with the smell of frozen waves. She asks for favor for her family, and that Little Cedar be protected. She asks to understand her dreams.

The ice cracks and pings down the shoreline, echoing off the high cliff. There’s no moon on the water, just shadows of ice. Just sharp cold air against her forehead, and clouds of breath in front of her face.

2000

Nora reaches for the nail that holds the Christmas lights, her breath fogging against the mirror behind the bar, when something from her dream takes form, a feeling almost as much as an image, causing an empty swirling inside. She kneels on the bar stool and closes her eyes, hoping her mind might retrieve a scrap. But no. Nothing. It is usually like that, just a little sliver of something when she’s awake that had been part of something bigger. She moves her stool against the double-door cooler, bumping the new calendar that slides down on its magnet. January, again, already. The string of Christmas lights sags low—green, p

ink, yellow, blue—doubled and swinging in the barroom mirror as she lowers them from the nail.

There. She tugs her sweater down, her mood deflating at the sight of the mirror without the lights. They add a bright touch to the Schooner’s atmosphere, given the cold short days of a northern Wisconsin winter. Nora stands before the mirror, winding the string of lights. Her roots are starting to show again. She’s going to stick with the new copper color. It gives her more oomph than the brownish red. Reaching for her cigarette, she finds just a long piece of ash in the ashtray. It seems to always go like that, light one and get distracted or stuck at the other end of the bar. The clock reads 3:40 AM, bar time. Len won’t come to clean for a couple more hours.

There’s something about taking down Christmas decorations that always makes her feel empty. It’s like after the movies when the lights come on, the story’s done, and there she is, sitting with her coat in her lap. Sometimes she even gets the feeling at home in the silence of her apartment, after the TV twangs off.

Two by two Nora pulls bottles off the back bar to get at the strings of lights taped to the riser. The idea for the riser lights came years before, when her mirror swag fell in the middle of a rush. At the time, she was too busy to care, so she kept on working with the lights back in the bottles, and she grew to like the way they shone through. Pink in the vodka. A warm glow behind the brandy.

Well, it can’t be Christmas all the time, and cleaning’s the best way she knows to start over. The sharp smell of vinegar rises as it mixes with the steaming tap water. Nora pours herself a vodka, and with timing that is second nature, rights the bottle and reaches back, turning off the faucet.

Footsteps cross overhead, followed by the sound of a bench scraping across the floor. She smiles as she wrings the rag, then wipes the riser with long strokes, her attention on the ceiling, listening. Rose’s piano music drops down through the floor, slightly muffled and otherworldly. Angelic—the firm piano chords and the tinkly upper notes. The softest, sweetest sounds come from that tough old girl.

Nora hums and eyes the ornaments as she wipes the bottles and stands them back in place. The ornaments are everywhere—hooked into the netting that drapes from the ceiling with the glass floats and corks and the life preservers, hung from the rigging of the model schooner that’s displayed on its own shelf by the pool table. All around her, pieces of her history are dangling from thin threads. Nora swishes her rag in the bucket of water, wrings it, and wipes down the bottle of Crown.

The Indian girl with the papoose was a gift from Delilah, their best cook in the boom days, before the mines shut down. Those years were nearly fatal for the towns on the Iron Range. Superior got plenty bruised as well, with its railroad and shipping industry. But she’s not complaining, she’s been luckier than most. The last things to belly up in any town are its bars; well, its churches, too. She dumps the old water into the sink.

A waltz. The piano music feels just right as Nora pushes a chair around the floor, climbing up and down to get the ornaments from the nets. She unhooks the log cabin that Ralph, her late husband, made entirely of whittled sticks. Together for seven years, married for three. The cabin twirls in a circle from an old piece of leather. That’s twenty-four years she’s run the bar on her own.

She climbs down and sets the ornaments on a table. The silver angels holding hands like paper dolls. The elf on the pinecone from her sister Joannie in California, reminding her that she needs to mail a birthday gift. The old rusty red caboose. She’ll wrap them each in tissue paper and tuck them snugly in a box, like little children off to sleep.

Nora slides the chair up against the jukebox to get at the ornaments hung from the old bowsprit. The glass bird looks like it swallowed the pink jukebox light. It came in on a salty all the way from Greece. She smoothes the bird’s feathered tail between her fingers, then unhooks her daughter’s plaster handprint, painted green and red but only on one side. She’d thought about having her granddaughter make one so Janelle could hang them side by side on their tree. She’d even thought of making one herself, a trio going three generations. It was a good idea, but she never made it happen. They were barely in town long enough to open gifts as it was.

The music stops abruptly. The bench scrapes out.

Nora climbs down from the chair, holding the Santa straddling an ore boat that John Mack gave her. It’s been two years now, and the bar is still absorbing his death. When in port, he was a fixture—last stool on the left—always trying to start up his debate: Lake Superior, is it a sea or a lake? Telling his sailing stories to anyone who’d listen: sudden storms coupled with poorly loaded freight, nasty tricks played on green deckhands. She wraps the freighter in a piece of crumpled tissue paper, seeing his speckled blue eyes, how they’d draw people in as he spun his tales. Landforms changing shape. Strange sounds from the horizon. It’s still unbelievable that after years on those freighters, he fell out of his fishing boat and died of hypothermia. They found his body the morning of her fifty-fifth birthday.

The sky through the window is tinted orange from the glow of the neon Leinenkugel’s sign. Nora opens the door to the empty street and the steely smell of winter coming in from the ore docks. Lake Superior may bring in her business, but it’s heartless; you wouldn’t catch her on it for anything.

It’s snowing again, tiny flakes like salt, dropping through the streetlight halos. There’s not even a car to be seen, not a single black track on the street’s white surface. The tiny flakes drop down from the blankness, landing on her sweater and the toes of her shoes. The chimney on the VFW is a silhouette against the sky. There was something in her dream. She’s carried it all day.

Nora feels the cold air reach her lungs, feels the particular time of night where it seems like she’s the only one awake, the only witness to the snowy street, to the air blowing in from the frozen harbor, and the small falling flakes that are touching everything.

1902

Snow sweeps past the window on a northwest wind coming down from the hills toward the lake. Berit feels like her cabin is a rock in a river, the way the wind rushes past on either side, full of snow and icy crystals. She turns from the back window by the bed to the front one that looks over the water. The snow is flying nearly horizontal, blowing out over their frozen cove, reaching the open water in dark strips of agitation that chase, one after another, toward a vague grey horizon.

Down at the fish house the window is blank. Gunnar hasn’t lit his lamp. He is bent, she is sure, over his task, straining his eyes and leaning in some posture that she will have to rub out of him later. Sometimes she wishes he’d slow down. Everything in sight, he built single handedly. The fish house is a beauty—two stories, and now the new net reel standing beside it to replace the one that the gale took last year. Extra things, too, that he makes just to please her, like the bench out at the end of the point, where she can lean back against the old pine. “You can sit there and watch your lake,” he teases. But it’s true in a sense, the lake is hers. First, she lived on Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula, then Duluth, now Minnesota’s North Shore.

A gust of wind hits the cabin so hard that Berit feels like she’s been shoved. The hill is in full whip and bend, the pine boughs winding back and forth as if hurling invisible stones, and the birch she’d admired just that morning, sweeping down the slope like a wedding veil, have completely turned in temperament. They lurch, bend, and jostle together, knock and stir like an army of skeletons. She holds her hand to the chinking between the logs to feel for any biting lines of cold. Wedding veils to skeletons. Her thoughts do grow strange.

The smell of bread is a comfort with the storm coming down, and she’s glad it’s baking day as she wipes the spilled flour from the tabletop, strip by strip bringing back the wood planks, the wet wood making her think of spring, as most anything does these days. It will be a relief when the steamship starts running again. Steady mail and fresh supplies. She swishes her rag in the tepid wash water. Four years they’ve been up th

e shore. She thought the isolation would get easier. She pauses, frowns. She thought there would be children.

Again, she finds herself stationed at the window, her damp fingers touching the cold glass. Soon the steamship will dare venture out. Just knowing she’ll pass by regularly makes everything easier, marks those days apart from the others, even if it’s just Gunnar rowing his fish out, to be transported back to Duluth. She closes her eyes—the boat’s heavy bow plying the icy water of the lake. She can almost hear the low drub of her engine, the way it bounces off the rocks.

Her fingers leave small marks on the windowpane and she touches their cold tips against her cheek. She must stop indulging this way. It only makes it worse and the boat slower in coming, but her mind is as reinable as the wind on the water, and her thoughts rush out one after the next. News from her family on the Keweenaw. Fresh coffee beans. A sweet squirting orange.

A stream of snow is blowing off the roof of the fish house, where finally, the lamp is lit. She’ll bring down a piece of fresh bread on her way to fetch water. Berit surveys her cooling loaves, smelling the deep rye and yeast. She’d love to plunge her hands right in, wear a loaf around like a fancy muff. She’ll cut a thick piece from the best-shaped one and bring it to Gunnar still warm.

Gunnar glances up from his net seam to see Berit in her dark coat, making her way down the snowy path, buckets in one hand, a dark bundle in the other, walking with her crooked limp that he loves. His Mrs. with something good for him, braving the wind to make a delivery. Already his mouth is watering, thinking of all the baking she’d done. The door opens with a wave of cold air, and there she is stamping her feet, a long strand of hair flung across her red cheeks, her grey eyes blinking away the snow.

“It’s blowing,” she says, nudging the cat from her leg.

The Long-Shining Waters

The Long-Shining Waters